Blast from the Past

Our backyard birds are an excellent teaching tool, but what about their long-gone relatives? Extinction challenges students to think about evolution, conservation, science, and history. The birds of the past provide perspective on the world today and the effect humans have on it. While our focus is on extinct birds, these stories and activities tackle themes of conservation, adaptation, and how we can help keep our backyard birds common.

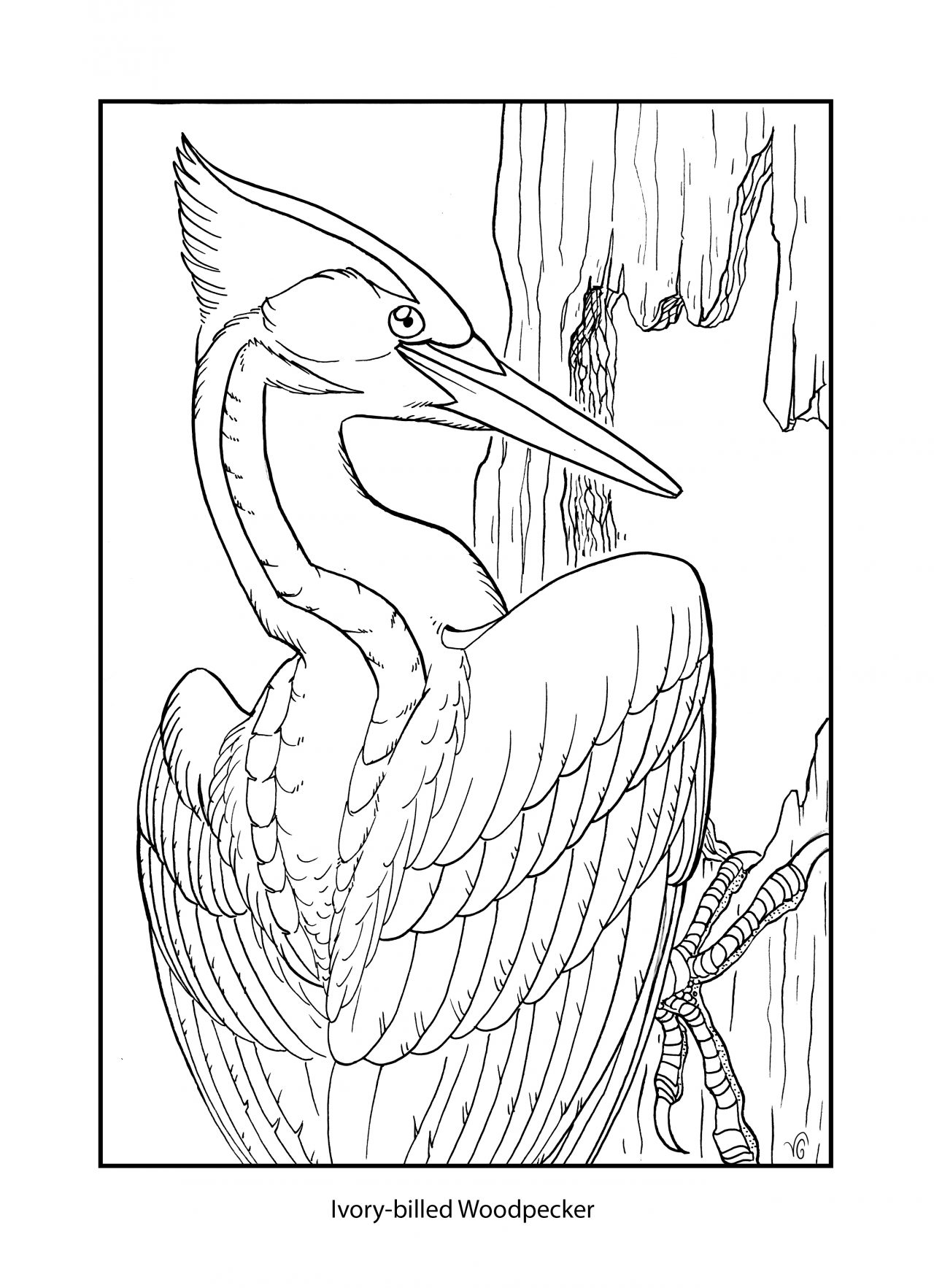

These printable coloring pages were provided by the talented Virginia Greene.

Archaeopteryx

When fossils of Archaeopteryx were discovered, they were the first fossils with recognizable flight feathers, leading to it often being referred to as the “original bird.” It was about the size of Raven and its features suggest that it spent much of its time gliding and hopping between trees and ground. Despite its bird-like qualities, it is also remarkably similar to dinosaurs with its hyperextensible second toe, or “killing claw,” and toothed jaws. It is still unknown whether Archaeopteryx was really able to fly or just glide from heights, but it is one of the clearest links between moderns birds and dinosaurs.

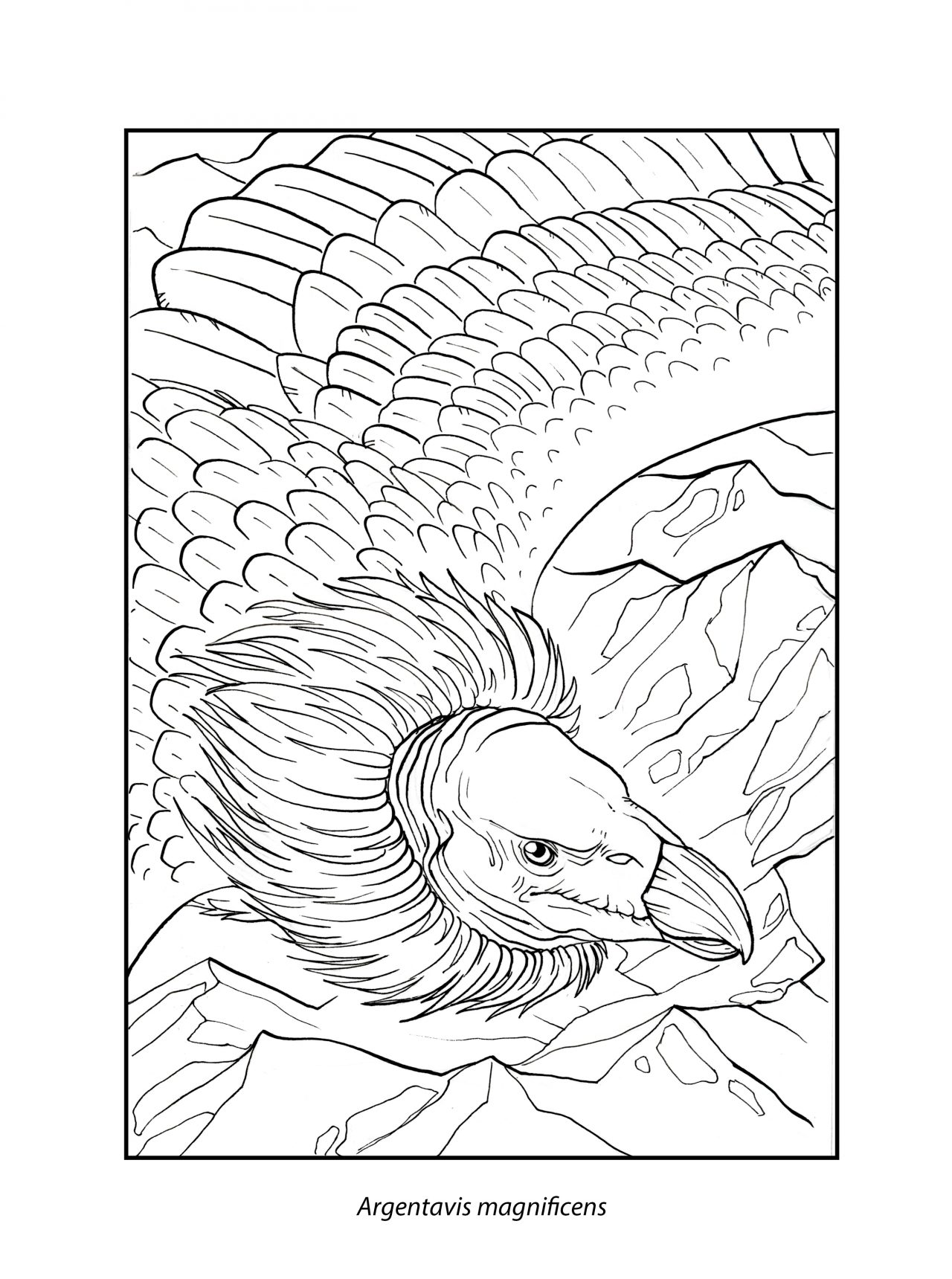

Argentavis

Argentavis was a massive raptor-like bird with a long hooked beak and stout legs. Their diet seems to consist of prey and carrion, which they would stalk on the ground or sit motionless and strike. Their wing bone structures are remarkably similar to those of the present-day California Condor and Bald Eagle, and they likely have very similar flight patterns using thermals to soar. These birds were enormous, with wingspans of up to 25 feet! It seems that Argentavis went extinct about 10,000 years ago, when most of North America’s largest animals went through a period of mass extinctions.

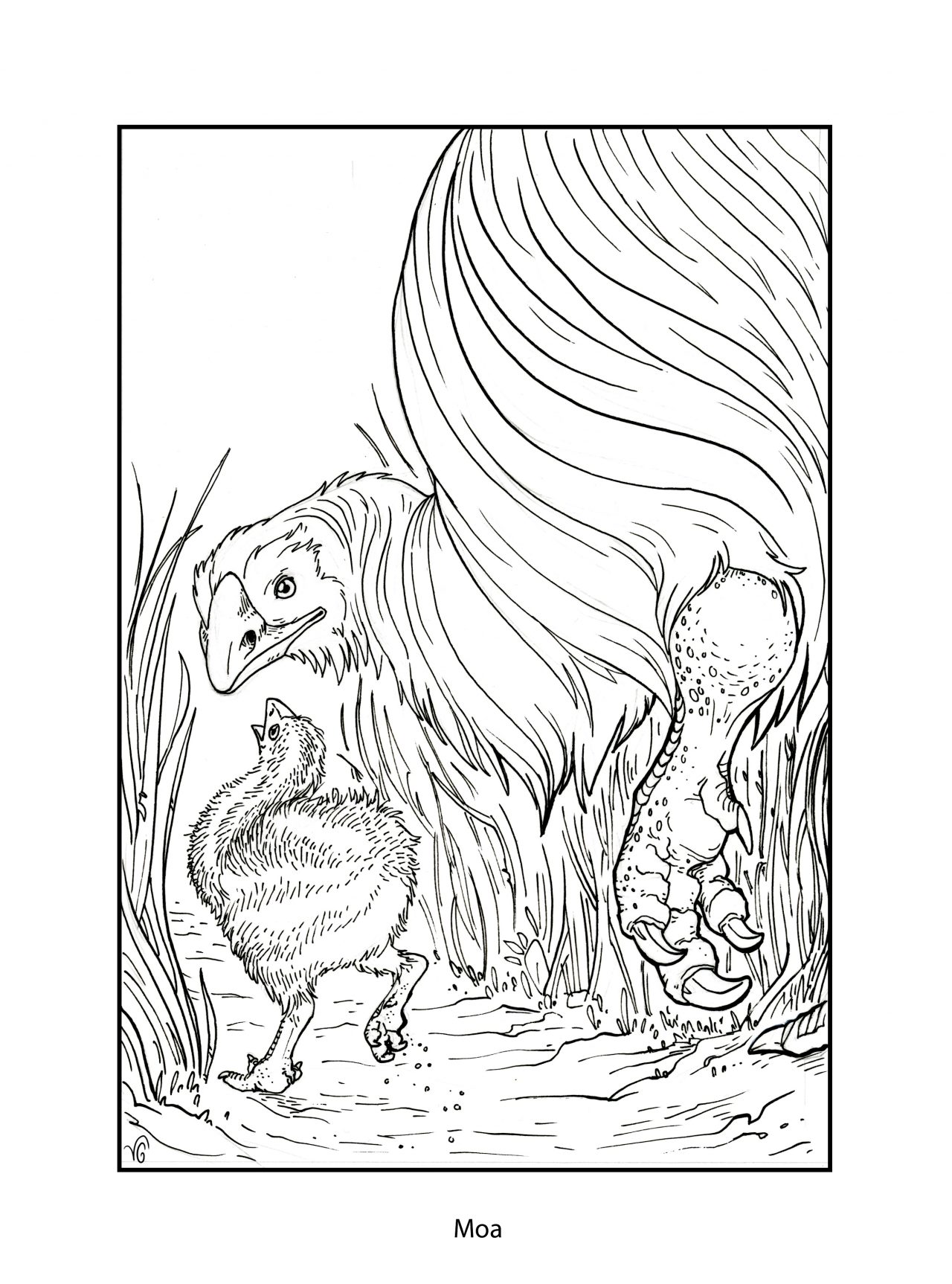

Moa

Standing tall at 12 feet, the Moa were flightless birds and the dominant herbivore in New Zealand for thousands of years. Due to their large size, they had few natural predators. Despite this, the Moa are also known to have the most fragile eggs of any bird to date. Because New Zealand is secluded, its animal inhabitants were unprepared for the arrival of the indigenous people around 1300 CE. Following the arrival of humans, Moa were hunted to extinction by 1445.

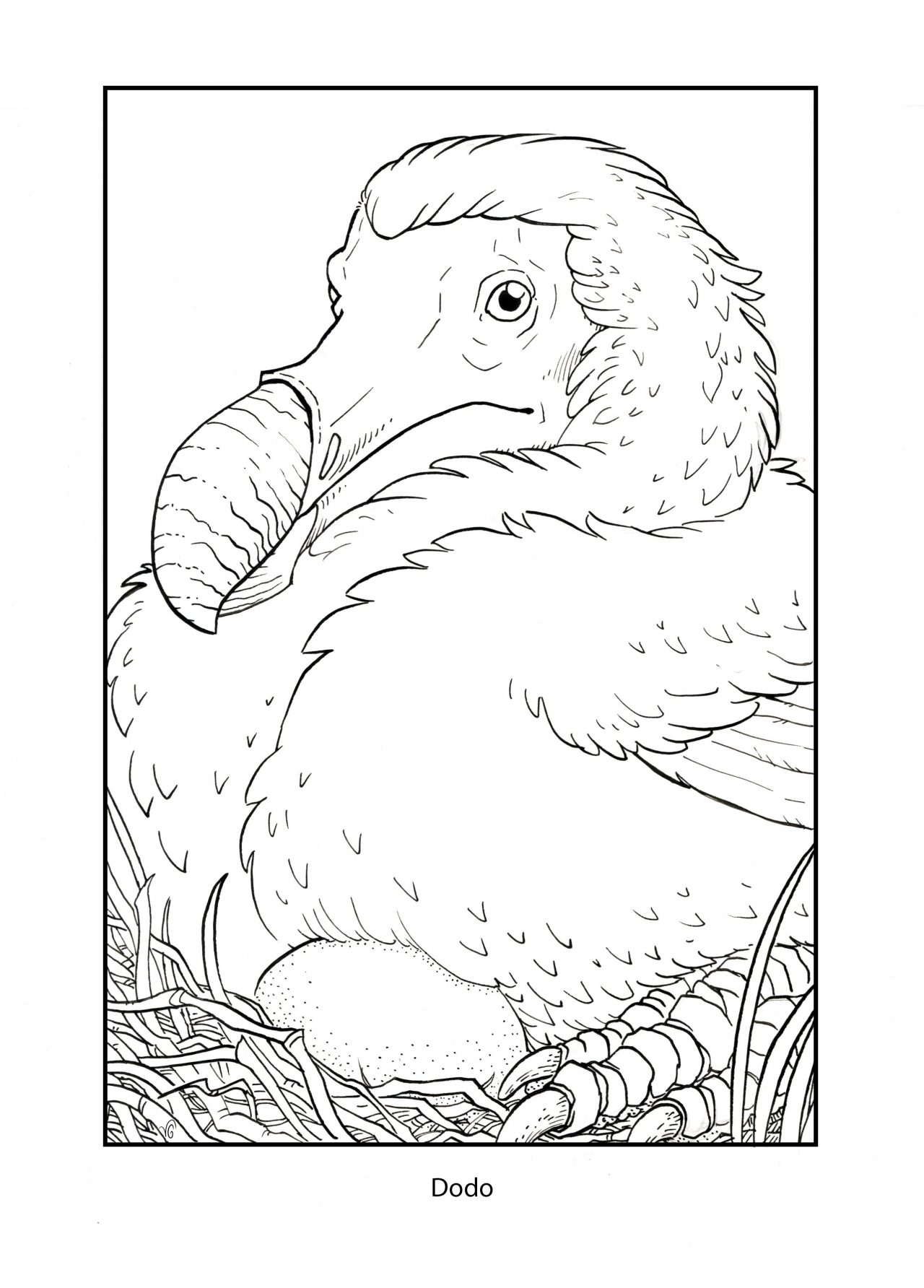

Dodo

Another flightless bird, the Dodo was said to be swift on land. Interestingly, we have little idea what the Dodo actually looked like due to few comprehensive fossils. We do know it was chubby and clumsy. With no natural predators, the Dodo lacked fear of people and was easily hunted to extinction by sailors for food by 1662.

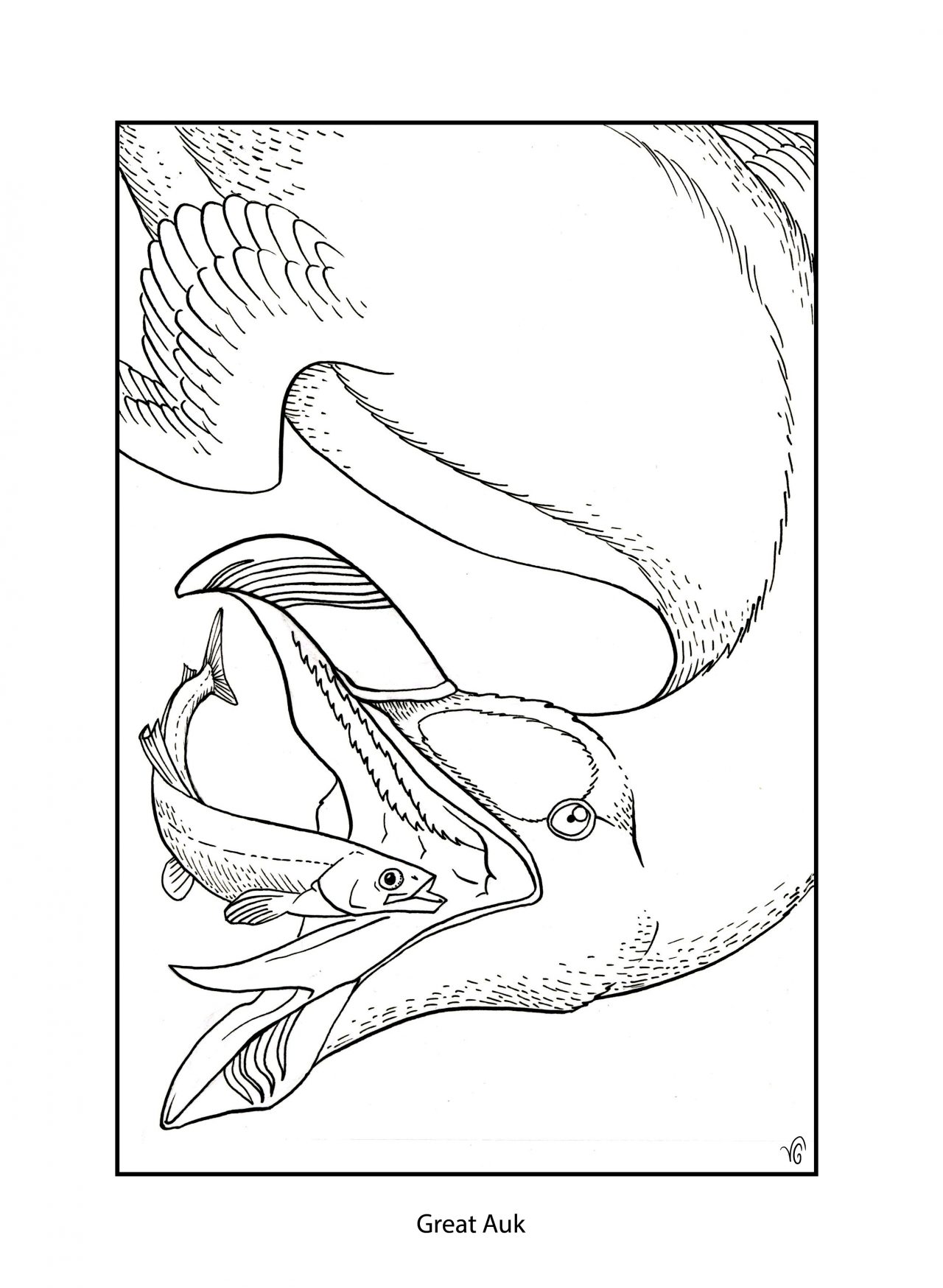

Great Auk

As an awkward, flightless bird on land, the Great Auk overcame this challenge as an agile swimmer. They were gifted fishers with their large hooked beak and lived on the islands of the northern Atlantic Ocean. Although they had previously been hunted by natives, in the 16th century they became valuable in Europe, leading to mass hunting. As the birds became increasingly rare, collectors began killing adults and eggs for specimens, quickly finishing off the population. They were declared extinct in 1852.

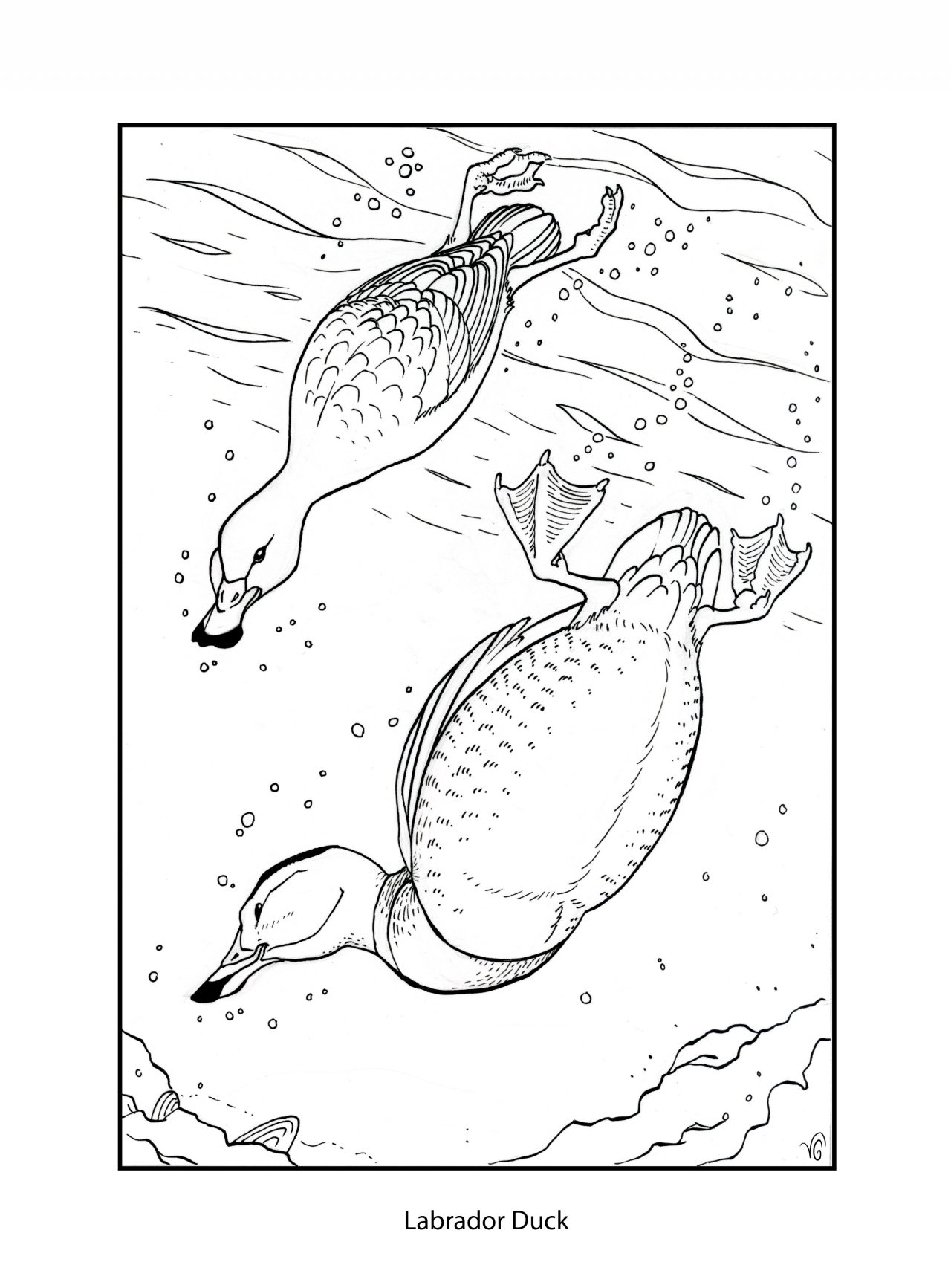

Labrador Duck

The Labrador Duck was a North American duck that was already relatively rare when Europeans arrived. There is little known about them for this reason, but they began to decline rapidly when Europeans moved into the area. Settlers over harvested their eggs and depleted their main dietary sources of mollusks and shellfish, eventually causing the extinction of these rare birds in 1878.

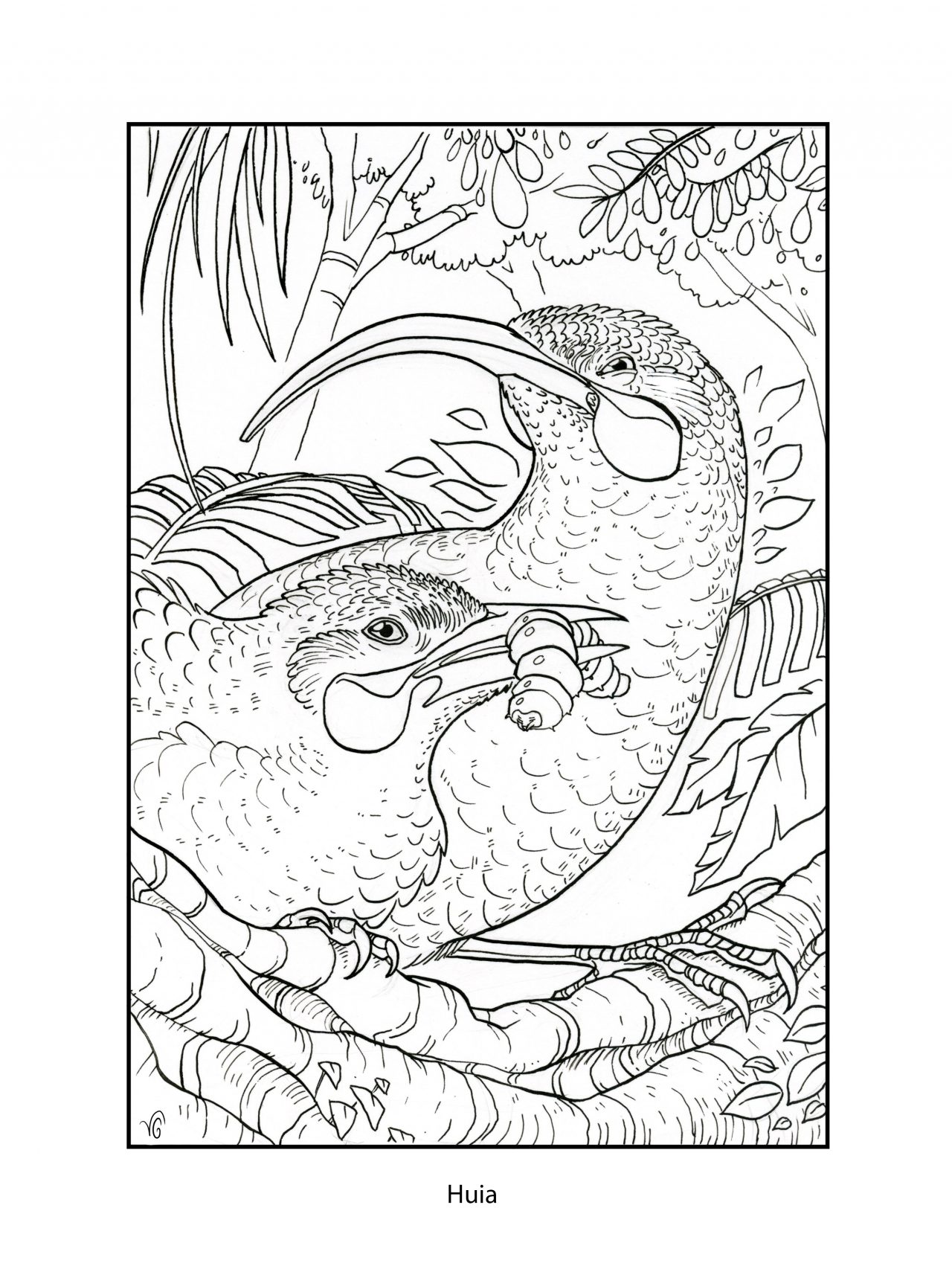

Huia

The Huia was a unique wattlebird that lived in New Zealand. The males had a short beak like a crow’s and the female had a long, curved probing beak, both for breaking into rotting wood for insects. They were treasured by the indigenous people of New Zealand and its feathers were often worn by those in high power. The Huia were driven to extinction in the early 20th century through a combination of deforestation and increasing hunting due to the value of stuffed specimens. The last confirmed Huia was seen in 1907.

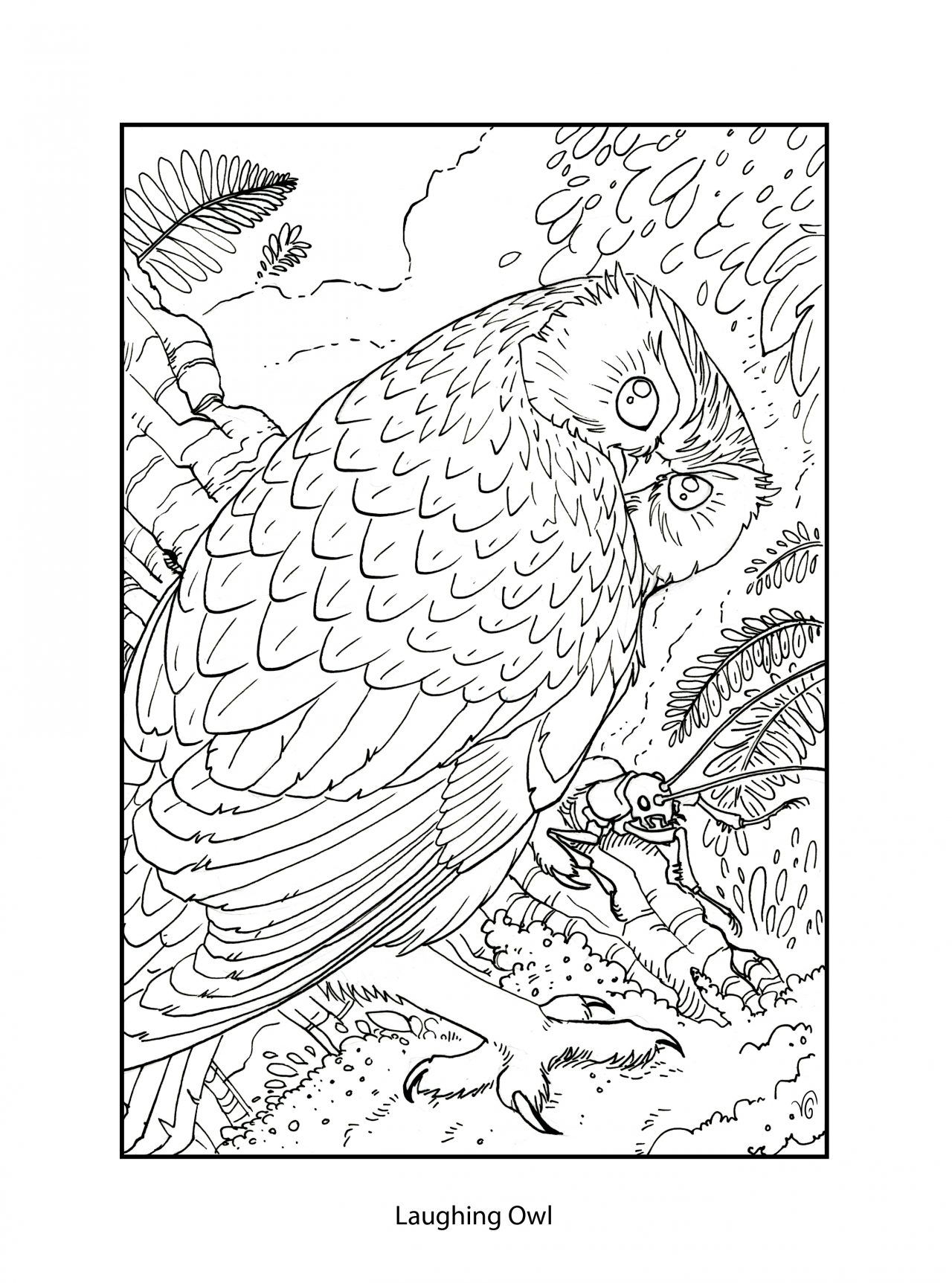

Laughing Owl

Also known as the White-Faced Owl, the Laughing Owl was a species native to New Zealand. It had a call similar to an accordion, and was named after these bizarre vocalizations. They preferred chasing prey on foot as opposed to flying like most owls. The Laughing Owl population declined due to predation and competition from introduced species. They became so rare the rest were killed by collectors for specimens. They were declared extinct in 1914.

Passenger Pigeon

Once the most abundant bird in North America and perhaps the world, these pigeons congregated into massive flocks to travel and nest together. “Safety in numbers” was this species key to survival until it encountered humans. In the 19th century they were exploited by humans in mass quantities for commerce and sport until there were few left, the last individual died in 1914. This species went from an estimated 5 billion individuals to zero in forty years.

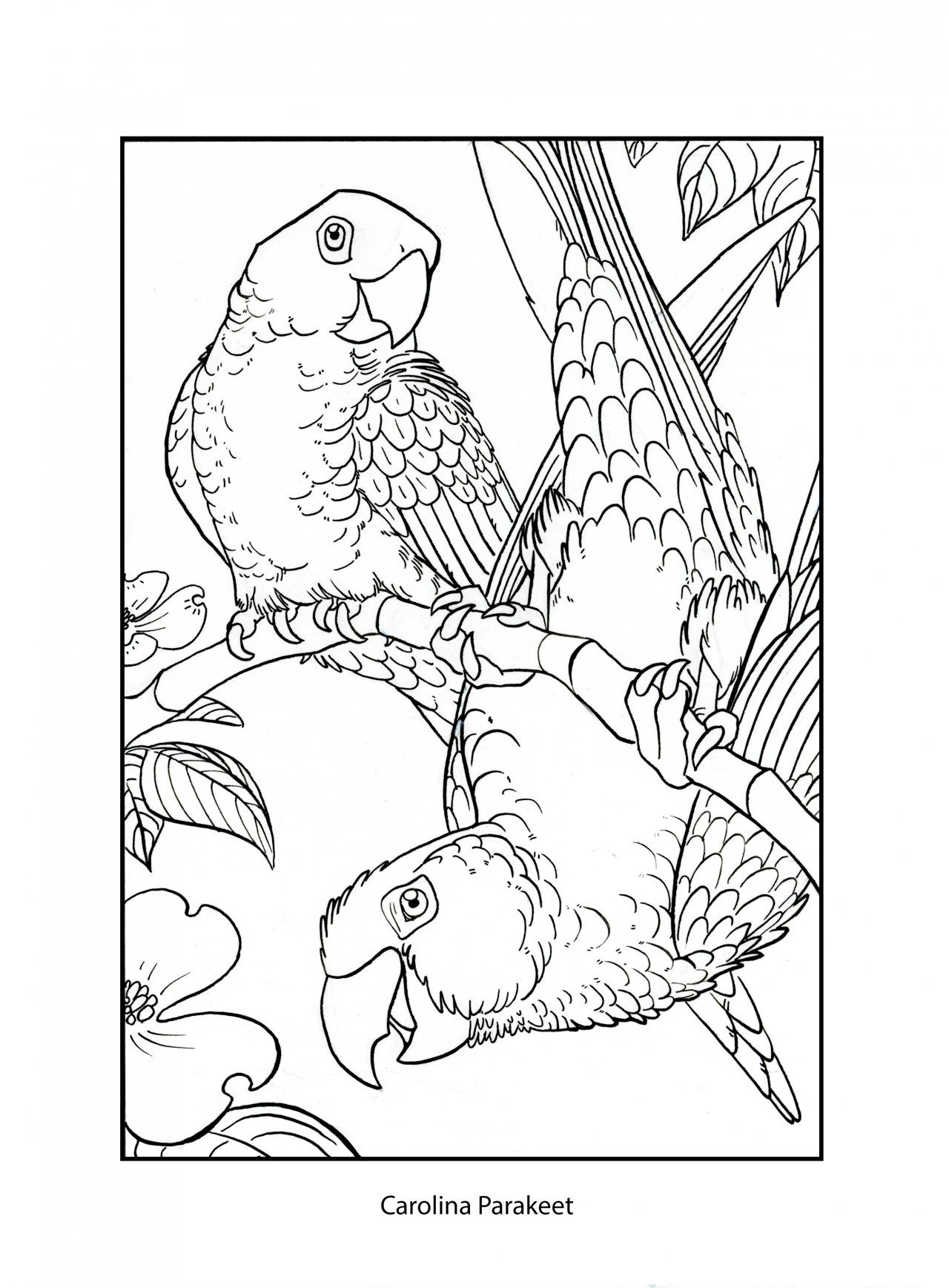

Carolina Parakeet

The Carolina Parakeet was the only parrot native to North America north of Mexico. They were sociable birds, forming large, noisy flocks outside of breeding season. Often considered agricultural pests, they were killed in huge numbers by farmers which, combined with progressive deforestation and being hunted for their bright feathers, led to their ultimate demise. Their decline began in the 1800s and were considered extinct in the 1920s.

Ivory-Billed Woodpecker

This bird was the third largest woodpecker in the world and lived in the old growth forests of the Southeast US. Destruction of its forest habitat led to substantial decline in the 19th century, and a controversial sighting in 2005 was believed to be the last of its kind. These large woodpeckers are listed as critically endangered and have proven very challenging to find and thus there have been no confirmed sightings since 2005.

Guiding Questions

- What are common causes of species extinction, both historically and today?

- Dig into mass extinction events (periods of widespread and rapid decreases in Earth’s biodiversity) and the causes for these events.

- What do these bird species have in common, if anything? (Note that many of these bird species are flightless. Endemic species- species that are restricted to a relatively small area, especially those on islands- are especially vulnerable to extinction.)

- Ask students to write a report on a bird (or other animal) that is currently endangered. What traits make this species vulnerable? What threats does it face? What conservation actions are being taken? Compare and contrast the endangered species that students write about.

Related Activities

1. Color the Past

Next to each of the birds listed above, you will see line drawings. Click, download, and print these pictures to use as coloring pages! You can use these as a stand-alone activity, or combine them with other projects or lessons. These pages are a great way to bring up the topic of conservation to your students and get them interested in extinct birds.

2. State of the Birds

The 2016 State of the Birds report is a great tool to show students the progression of endangered species and how we can save them from extinction.

Have your students identify their local habitat. Once you’ve decided where you fit on the map, use the Species Assessment Database to sort by breeding habitat and choose a few of the birds marked with a “Y” on the right hand column. This “Y” signifies the bird’s status on the “watch list,” meaning this species is at risk of eventual extinction if no action is taken. Let the students research some of these watch listed species and discuss with each other the similarities they might share with the extinct birds in the list above. Such characteristics might be cause of decline (loss of habitat, invasive species, pollution, etc.), species similarities (similar behaviors and niches), and human relationships (commonly hunted, protected, etc.). Discuss with your class the ideas of conservation and keeping our common birds common and working to save and protect those species threatened and endangered. Use the “change” page on the website and help the students identify changes they can make – either as a class or at home – to help save birds from extinction. Some ideas to implement in the classroom might be putting up a hummingbird or seed window feeder, modify windows so birds will not fly into them, stop use of poison or pesticides in pest control, or plant native or pollinator friendly plants in a school garden.

3. “Fold the Flock” – Passenger Pigeon

The Passenger Pigeon is a model for the importance of protecting our common birds. It went from the most common North American bird to extinct in just forty years. The website Fold the Flock is a great resource in teaching students about this infamous extinction through a fun Passenger Pigeon origami project. This is a great resource to engage students in conservation. Show your students the videos on the main page of the website to help them understand the abundance of the Passenger Pigeon prior to their decline. Discuss and connect this with common birds we have today. Can you imagine if their were no more gulls at the beach? What if all the crows disappeared? Have them each fold their own Passenger Pigeon to remind them of the importance of protecting their local birds (printed origami paper can be purchased, downloaded for free, or use blank paper and have students draw their own!).

4. The Wall of Birds

Introduce your students to Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Wall of Birds mural. Allow them to explore the birds of the world through the interactive photos and information on the website. Discuss the role of evolution that led from the grayed-out species to those that are still around currently. Point out specific birds on the map that are in danger of becoming extinct and how their presence is important.

5. The Great Backyard Bird Count

One of the most important and easy things we can do today is to help scientists keep track of our local bird populations. Through the Great Backyard Bird Count, you and your students can contribute to research involving the effects of changing environment and resources on bird populations via citizen-science projects. All you have to do is record data for at least fifteen minutes sometime between February 17th and February 20th, 2017. If these dates don’t work with your schedule, check out ongoing citizen-science projects like eBird and Project FeederWatch.

By using citizen-science projects in your classroom, students will get to have a real impact on conservation and saving birds. Explain to your students how their work will contribute to conservation and research. Use the list of birds in your area provided on the website and have students familiarize themselves with those species (you could split into groups or assign a bird per student if you have enough) so they can identify them during your bird watch. Follow the instructions on the website on recording and submitting your results. After you participate, have your students research other citizen-science projects and discuss how individuals can contribute to conservation research. Check out eBird’s data page and explore different maps and graphs showing the impact of the project. Show your students articles like this one on Chickadees to illustrate the use of citizen science in conservation.